One of Mike’s gt.gt. grandmothers was a woman called Sara Corner.

Sara was married to Michael Wimmer Jr. – the son of Michael Wimmer, an Austrian-born missionary who trained in England and lived in South Africa from the age of 47 until his death aged 79.

It turns out that Sara was also the daughter of London Missionary Society (LMS) missionary assistant(and a colleague of Michael Wimmer) called William Folger (variously Forgler or Frogland) Corner.

Unlike Michael Wimmer though, William Corner was not some middle-aged or European man, but rather a freed slave from Demerara (nowadays known as Guyana) in the West Indies.

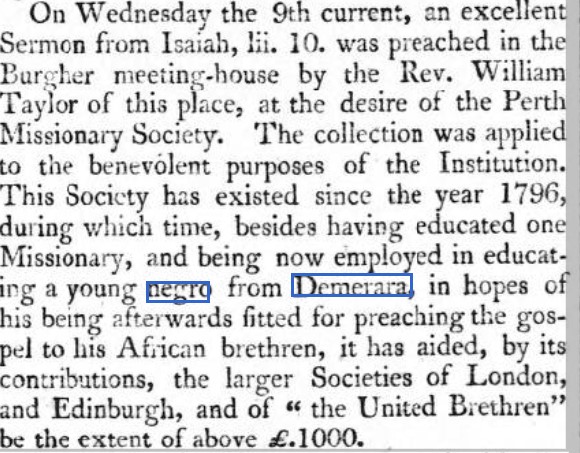

So how did a freed slave come to be carrying out mission work in South Africa? It turns out that William had been sent as a child – by a missionary, or some other evangelically-minded person in Demerera – to Perthshire in Scotland for his education. There is a newspaper article from 1809 which talks about the Perth Missionary Society being in the process of educating a “negro” from Demerara so that he can work in the missions. I am assuming that is William Corner.

There are records showing that he was a “mulatto” child, that is a child of mixed race, but as to the exact circumstances of his birth and his early childhood. Probably he was the son of a black slave and white father.

There is a strong history of Scottish links with Demerara and it was not unknown for children born to slave mothers and white fathers to be sent to Scotland for their education.

I don’t know exactly where he was educated, but at some point he was recruited by the London Missionary Society (LMS) to be missionary assistant and on the 21st June 1811 he set sail for Cape Town, arriving on the 13th September that same year.

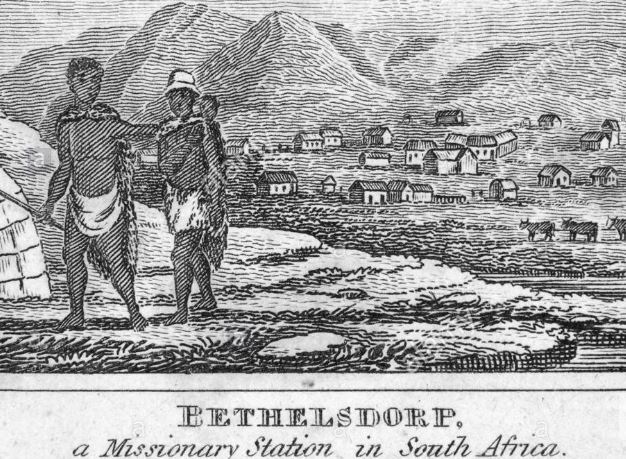

He arrived at the mission station of Bethelsdorp on the 13th April 1812. Bethelsdorp (near what is now Port Elizabeth) had been established in 1802 by the early missionaries Johannes Theodorus van der Kemp and James Read. Bethelsdorp has been referred to as being no more than a refugee camp housing some 600 indigenous Khoikhoi people.

As Michael Wimmer was also at Bethelsdorp at that time, this would have been when they had first met.

In 1814, the LMS decided that they need to carry out their mission work further inland and established a mission station at Toorberg (Thornberg) (now Colesburg) some 500km north of Bethelsdorp. It sent William along with the missionary Erasmus Smit to lead the mission station. In 1816, the LMS established another station at Hephzibah (near present-day Petrusville) a further 100km inland. William was called to work here along with an indigenous convert by the name of Jan Goeijmans: who would later become his brother-in-law.

However, tensions were running high in the region between the Cape administration and missionaries, and in 1817 Toorberg and Hephzibah were closed and William was returned to Bethelsdorp.

This was not the only problem for William.

In addition to the tensions between the LMS and the Cape Colony administration, there were tensions within the Society itself. Whilst the early missionaries had developed a somewhat radical approach to their role and supported local people, a section within the LMS sought to maintain what they saw as a more ‘respectable’ profile aligned with the colony administration.

This came to a head in 1817, when a conservative LMS missionary – George Thom – called a synod to discuss what was called the ‘immoralities of the missionaries’. The synod sought to establish proof of a dysfunctional set up within the society with a view to removing the older, established missionaries that Thom and his circle felt were causing trouble with the establishment of the Cape Colony administration.

At the synod, charges were brought against missionaries James Read, Heinrich Schmelen, John Bartlett (William’s brother-in-law), Michael Wimmer, and also William himself.

In relation to William, the synod heard that he had had a sexual relationship with his housekeeper in 1814.

An outcome of the synod was to (an extent) stigmatise interracial marriages and impose a more conservative regime in the operation of the LMS missions in South Africa.

As for William himself, in 1815 he married Elsje Goeijmans, a local woman whose sister Johanna had married the missionary John Bartlett. They had a number of children, although details are scant.

In late 1818 a local woman turned up at Bethelsdorp mission from a local farm with a five-month old baby. The lady claimed that William Corner was the father, and William admitted as such. The baby was born around the time that his wife had herself given birth. As a result, William was privately suspended from the LMS but the issue was not made public: one of the reasons given for this was that his wife was an extremely jealous person and they did not want to incur her wrath. Perhaps he had a track record of extramarital affairs that contributed to her jealousy !!

He is recorded as having left the station at this point, but we don’t know where he went. According to the death notice of his son, William Ogilvie Corner, who was born in 1820 at Colesburg, this suggests he returned to the northern reaches of the Cape Colony after leaving Bethelsdorp.

In 1821 he was formally dismissed from service of the LMS.

It is recorded that, in 1866, William petitioned the Orange Free State authorities for money due to his decades of work as a carpenter and teacher at Philippolis – a mission station founded in 1823 to serve the Griqua people and where a Griqua leader called Adam Kok II settled in 1826.

It’s probably fair to assume that he ended up at Philippolis some time after he left the LMS.

As we know, William had a number of children: exactly how many I’m not sure. One of his sons was William Ogilvie Corner, who I have already mentioned was born in 1820, and another a girl called Elizabeth Jessie was born in 1835 and, according to records in the same month as Sara. Were Elizabeth and Sara twin sisters, or just coincidentally two half sisters born at the same time? Elizabeth was born in the Orange Free State: probably Philippolis, so perhaps that is Sara’s birthplace too.

I know no more about William. I have no record of his death or where he lived at the end of his life. We know he was still around in 1866 and probably living in the Orange Free State. We find further records of his son William Ogilvie Corner as he played a role in the creation of the Orange Free State and the land disputes of the mid-19th century.

I’ll follow this up on another blog.